Thanks, etc.

Nothing I can say tonight will be as entertaining as Mayor Giuliani...

I’m honored to join you. I know that I follow many more distinguished speakers, but I did receive this note from my doctor…

TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN

Scott is the healthiest person ever to deliver the Herb Block lecture…

My family is here…

Our daughter Elise is joined by our friend, Adelaide Machado-Ulm, who has just started on their school newspaper. Elise is on the yearbook. So, that’s the first draft of history, and history. Elise and Addy will be glad to review your resumes at the end of the evening.

Of course, we’re here because of the vital work of the Herb Block Foundation, which Herb secured with his bequest of tens of millions of dollars earned during his career as a cartoonist. So Elise and Addy—I think the lesson is: stop writing, start drawing. That’s where the real money is…

(Ward—is that standard salary for a cartoonist?)

I am honored to share the stage with Ward Sutton. His cartoons in the Boston Globe, and those under the moniker of Stan Kelly in The Onion reveal a great stylist and satirist, who merits comparison with the man whose name is on the award he takes home tonight.

And let me just add: I speak for myself tonight. Not my employer. Not even my family. Perhaps especially my family.

But I believe nothing I say will mean I can’t be a fair reporter. One of the differences between covering the news in blogs and tweets and doing it for a living is professionalism. We all have personal beliefs—though it’s been my experience that there is nothing like journalism to shake up the beliefs you thought you had. But we can do our jobs and report fairly.

I wrote to Herb Block when I was in high school. We would see Herb’s drawings, two or three days later but still timely and pertinent, re-run in the Chicago Sun-Times. He lampooned Richard Nixon’s duplicities, lamented the loss of Dr. Martin Luther King, and put his pen and inkpot into the argument for civil rights.

Herb—along with Clayton Moore, who was The Lone Ranger, and Bill Friedken, the director, Shecky Greene, the comedian, were the the most notable graduates of Nicholas Senn High School in Chicago; although locally Herb and the rest of us fall behind a score of beloved organized crime figures.

I played on the Senn connection. Improbably, Herb wrote back. I was then putting out what we called an underground newspaper in high school, and wrote back to Herb to thank him for his thank you note, and to ask him, Sennite to Sennite, for an interview. Astoundingly, he agreed and sent me a phone number.

My memory of that interview is anecdotal. I know it was short, because long-distance was then costly; I kept looking at the second-hand on our kitchen clock as Herb ruminated. But I asked him about one of his most famous cartoons, from the eventful year, 50 years ago, of 1968.

Herb had famously portrayed Richard Nixon with a swarthy, almost piratical beard. That lugubrious growth became an artistic emblem for Nixonian duplicity and thuggery, especially during the McCarthy era, which no stage make-up could conceal.

But Herb told me he had heard that Richard Nixon would snatch the Post from their front stoop each morning when he had been Vice President to hide it from his daughters; so they wouldn’t see their father depicted as a shady character. He wasn’t a shady father. Herb was unbowed as an artist and commentator, but touched as a human being. And he thought he had made his point, time and time again.

Herb Block was pointed and professional; but he wasn’t petty. He understood that politicians had a job to do, and so did he.

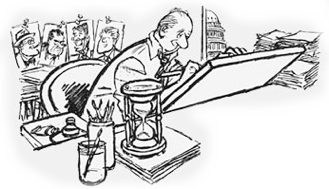

And so when Richard Nixon was elected president in 1968, Herb famously drew his own drawing board, brushes, and ink-pot below a sign that said, “This Shop Gives Every New President of the United States a Free Shave.”

Herb told me that although he’d been in the nation’s capital for decades by then, he still thought of himself as a guy from the north side of Chicago, and tried to view people as people, not just political positions.

I try to remind myself of that some times.

There is another cartoon from 1968 I discovered a few years ago. Herb showed a man knocking on the door of a comfortable home. You look a little more closely, and you see the man looks like Uncle Sam—but he’s painfully skinny. He holds a report issued by a presidential commission on hunger in America. The man in the home who sits in an easy chair tells him, “You must have the wrong address. This is a very prosperous country.”

The art and audacity for Herb to use the reflection of an American symbol to shake the conscience of the American people.

I also got to interview Herb as an actual reporter in the 1990’s, and he talked about the fact that he had left school to begin drawing cartoons at the Chicago Daily News in 1929—the very year Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur of the Daily News debuted their classic play, The Front Page.

I suspect this was a play many of us have loved; although you have to be selective in your affection for it today. It portrayed a news business that was bustling, creative, roustabout and fun; and absolutely not inclusive, often casually bigoted, despicably sensationalist, and routinely boorish.

But those under-educated, maladjusted, overbearing, and often-debauched news people also helped create a vital, competitive, and populist news industry. This was something new and distinct to America: journalists who weren’t the voice of and didn’t work for any political party or movement. They reported for a living.

The great Daily News columnist of that era, Finley Peter Dunne, coined what became known as a motto for Chicago and perhaps for American journalism. He said—and he wrote in an Irish-American dialect we should probably avoid these days—that the job of journalism is to afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted.

And we do say job. Those of us blessed to do this as our life’s work also have to know that to make it work, we have to make it pay enough to keep going.

I have always felt a little awkward at awards ceremonies when American journalists salute each other for “courageous reporting.”

That happens. But, however ugly the approach of the current administration, we are still blessed to live and work in a place in which we are free to do this work; and more likely to be honored for it than arrested, jailed, or defenestrated.

Russian journalists, including—and lets mark their names--Nikolay Andruschenko, Dimitri Popkov, Andrey Ruskov, and Maxim Borodin, who all died just within the last year under mysterious circumstances—they had courage. They investigated government corruption in a society that pushes them out of windows, not gives them awards.

Mexican journalists, including Carlos Rodriguez, Guamaro Aguilando, Edgar Castro, Candido Vazquez, Rosario Flores, Luciano Rivera, Edwin Paz, Salvador Pardo, Hector Cordoba…It’s a long list, isn’t it, of Mexican journalists who were killed just in the last year while investigating crime and corruption. They had courage.

The Afghan journalists, including Shah Marai, Ahmad Shah, and Yah Mohammed, who died last week in criminal attack intended to draw and murder journalists—they had courage.

We could also recall other local journalists who’ve died in Myanmar and The Philippines, or been jailed in China, Cuba, and Iran.

I’ve covered conflict overseas, in central America, Bosnia, and the Middle East, and felt in danger a few times; usually by my own miscalculation. But I knew I’d be safe if I got home. A lot of our colleagues in other societies are not safe especially in their homes. That’s where they've been pushed from windows, and slaughtered in hallways. We should hold them in our thoughts and hearts every day.

One of the truisms you can hear about these times is that we’ve never seen anything like this current administration, and its disdain for a free press.

We should be careful about that. Northern newspapers savaged Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War as a “baboon,” a “gorilla,” and a “butcher.” And Mr. Lincoln, who sits so nobly in marble just a few blocks from here, closed down more than 300 newspapers. He considered them to be subversive.

I don’t fear today today’s US government can shut down a free press. But for the first time since I became a working reporter, I am shaken by the sheer brute ugliness with which members of this administration, including and most notably the president, disparage, mock, and demean human beings, and make special targets of immigrants, ethnic and religious groups, whole countries, and yes, the press.

This kind of speech is just un-American. I don’t have a stronger profanity than that.

And I’m aghast that the administration so often uses the access they have to speak directly to the American people to distort, twist, deceive, and outright lie to the American people.

This isn’t just a politician who strives to put a positive spin on discouraging facts. It’s one of the most powerful officials in the world, who consciously peddles whoppers, like worthless swampland, or muddy lots in a David Mamet play, to the American people.

The scale of these fictions would daunt Charles Dickens. Placido Domingo wouldn’t have the breath control to repeat hem all.

The president of the United States slurred the father of Ted Cruz by suggesting he had a role in the Kennedy assassination. He boasted of having the largest inauguration crowd ever, when it wasn’t even a quarter of the size of the World Series parade for the Chicago Cubs. He’s continued to claim massive, fictitious vote fraud, and a landslide in the Electoral College, when it’s only the 46th largest margin, which puts him only slightly ahead of Zachary Taylor. He insists the murder rate in America is the highest it’s been in 47 years; it’s actually the lowest in sixty years, although, to be sure, it’s still too high.

The president apparently dictated his own fantasy of a medical report. His health has evidently improved dramatically in the decades since his bone spurs got him a medical deferment.

And the president told reporters straight to their faces that he didn’t know of any payoff to an adult film star for her silence.

What’s the word for that kind of brazen falsehood? A fantasy, a misstatement—or a lie? What would you tell your children?

The president also said the public approval rating of the press is lower than it is for Congress. That is also not true—but alas, it’s close.

Our role in response to these fictions is obvious and impossible to shirk: we report the truth, without fear or favor. We don’t do this to contradict the president—although, that’s fine--but to do our jobs.

I don’t want to be melodramatic about this current atmosphere and administration. There are lots of editors in this room. Reporters can be annoying as hell, can’t we? Don’t tell me you haven’t looked at a troublesome reporter, then looked at a window, and thought, “Hmmm…he’d just about fit…”

This isn’t Russia or China, where good reporters live under threat and assault and don’t have evenings like this, in the Library of Congress.

But a president that taunts and insults a free press, has condoned mob violence, and used the power to reach Americans directly to promote one whopper after another and bully people, spreads fuel on a fire that scorches democracy.

Just today the president ruminated aloud on Twitter about pulling the credential of reporters. I find that more naïve than sinister. Mr. President—it doesn’t take any credentials to be a reporter! Why do you think most of us are in this business? I don’t even have the credentials to be a licensed massage therapist.

In a way, I’d actually like to thank the current administration for giving us a chance to prove our value all over again. If we’re worth reviling so much, we must be worth something.

I think, for the first time in our lives, our daughters might believe I do something for a living that is vaguely significant.

We’ve been reminded, as professional politicians know, that reporters have their own professional responsibilities—“the Reporters’ Gallery yonder,” said Edmund Burke, “a Fourth Estate…”—that are as old as those of elected officials.

But I see another threat to the job of a free press that cannot be blamed on this administration: the echo chambers we have engineered for ourselves.

People can now choose the news they want. They need not disturb themselves with a story, a fact, or opinions that chance to upset their view of the world.

People who believe the moon landing was a hoax can find videos to support their preposterous view. People who believe the attacks of September 11 were a fraud, perpetrated by—choose your poison—the CIA, the Bush administration, Mossad, the House of Al-Saud, or the international Jewish conspiracy, can find support for this slander and think of themselves as a “community,” instead of lunatics.

People who chant, “Blood and soil,” an old Nazi slogan, on the soil of the United States of America—which has been nourished by the blood and lives of people from all over the world—can form their own e-world, sealed off from real humanity. Incels, as they call themselves in online forums, can tell themselves they’re aggrieved victims, and not loveless losers.

Millions of good and conscientious Americans now fill themselves with news they choose that only nourishes the views they already hold. In a way, it’s a return to the times when political movements parties sponsored newspapers.

People sometimes congratulate public figures, commentators or comedians, for speaking truth to power. But the fact is, more and more Americans from all political corners are happy just to speak to themselves, over and over, tweet after tweet, post after post. And people that talk to themselves, whether its mumbling to yourself on the subway, or echoing only people who agree with you, need help.

We’re using the power of the internet to connect us to the world, then close us off from different points of view. Too often, we use this dazzling information technology not to inform ourselves, but just to confirm whatever we’d like to believe.

Every day I get emails saying, “I don’t listen to NPR to hear…” And they finish the sentence with a point of view, a person or a group of people, or an area of interest they seem convinced will impart a fatal rash if they so much as hear of it.

It depresses me that after so many decades where good journalists have strived to try to bring a variety of opinions and experiences to people, so many Americans now choose to close their ears, hearts, and minds.

In these times, that command we take from our founding days to afflict the comfortable also means challenging the comfortable notions and nostrums our audiences may have about the world—left, right, and center.

Real journalism doesn’t just pat your audience on the head to say, “You’re right. You’re smarter than everyone else. Everything you think is right, and we’re going to help you keep thinking that way.” It’s having the nerve—and the respect, and professionalism—to tell an audience, “This story may shake your views. That’s what we’re here to do.”

And now and then we should remind our audiences: there is no safe space in journalism.

We should advise our listeners, viewers, and readers: in this space you will encounter words that rile and even offend you, views that appall and depress you, facts that defy your own views, reporting that upsets and distresses you.

That’s why we’re here. That’s why we think journalism is worth doing.

When we hear clichés—normalize, marginalize, the so-and-so community, empower, synergize—we should strike them out and speak with clarity.

When the powerful bully and slur, we should strike back with civility. And when they lie, we should correct them.

Back to The Front Page. When the play opens, Hildy Johnson, our crime reporter, is tired of his scruffy reporter’s life, and comes into the Criminal Courts pressroom to tell his friends he’s leaving. He’s getting married, and will work as an ad-man for the company owned by his fiancée’s father. And Hildy exclaims:

Journalists! Peeping through keyholes, running after fire engines like a lot of dogs, waking up people in the middle of the night to ask them for pictures of their dead loved ones, or what they think of Mussolini, a lot of daffy buttinskies running around with holes in their pants, and for what? So a million office workers and motormen and their wives can think they know what’s going on?

Sounds like a good life to me…

When presidents, politicians, other sources of power attack us, I don’t think we should profess to be offended or aggrieved.

Remember: this is the life we chose.

This president may seem more open and abusive in his contempt. But Abe Lincoln closed 300 newspapers. Woodrow Wilson signed the Espionage Act of 1917 that made it illegal to—quote—“utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States…”

That would put most of us here behind bars just for a Tweet.

And wouldn’t some people be happy to see that…

Richard Nixon had journalists on his Enemies List—including my eminent old colleague and friend, Dan Schorr.

President Obama blew the cobwebs off of Wilson’s legislation to prosecute more government whistleblowers than all previous presidents combined.

So as we confront the jobs we have to do in this era, let’s remember that journalists have been on this ground before. And it’s where we show what we’re made of. Or for copy editors in this room, it’s where we show of what we’re made.

This is a tough business; it should be. The stakes are real. We put a hand on events that can affect elections, reputations, life and death decisions, and events large, small, forgettable and enduring.

We’re in journalism, not the academy, a yoga workshop, or Zen monastery. Journalism is the profession of The Front Page, not Mary Poppins. It should and can be accomplished with civility and decency.

But journalism is also rough and tumble. It’s a contact sport, not a Montessori kindergarten. Our rumpled forebears in this business were among The Deplorables of their times: swaggering, obnoxious, sweaty, and rowdy. But they created modern reporting that opened news to the public, independent of party, lobby, or faction . They told stories about murders, riots, wars, crimes, bribes, revolutions, nonsense and inanities because it’s all part of our human story, and citizens of a democracy have the right to know and can be better citizens if they do.

Journalists are not descended from timorous tribes of people who cringe at criticism, or shudder at second-guessing—from a president, politicians, or even our own public. When there is carping, kvetching, and verbal assault from high places, we should keep in mind the example of Walter Payton, the great Chicago Bears running back: just take the hits and keep on going.

Thank you.

Herb Block is among the world’s best known and most admired political cartoonists. Born on October 13, 1909, the native Chicagoan spent his 72-year career fighting against abuses of the powerful.

Herb Block is among the world’s best known and most admired political cartoonists. Born on October 13, 1909, the native Chicagoan spent his 72-year career fighting against abuses of the powerful.